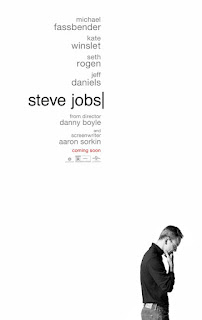

Steve Jobs

As I was walking out of Steve Jobs, a fellow moviegoer started talking to me about the film. He works at Tekserve, and has seen other movies about Jobs and Silicon Valley. As he spoke about his disappointment in the film, it became clear that he was heavily invested in the people portrayed, in the facts of the story told. I, of course, had different expectations.

I'm not into tech. I don't care much about Steve Jobs, though I understand and can appreciate the impact he's had on modern technology and the way we live our lives (i.e., tethered to the devices he created). I'm even writing this on a MacBook. But I cared less about the people being portrayed than the characters being brought to life, and less about the facts than the truth of the human story being told.

In these regards, Steve Jobs is a compelling film (and there's absolutely no reason it should be rated R, other than that the squares at the MPAA don't like the word "fuck"). I didn't love Danny Boyle's direction; there were actually too many close ups that were too close up (I know, I'm complaining about close ups of Michael Fassbender—I should go home), but Boyle (127 Hours) was able to pace the film just right, making three acts of people talking intriguing and exciting.

In these regards, Steve Jobs is a compelling film (and there's absolutely no reason it should be rated R, other than that the squares at the MPAA don't like the word "fuck"). I didn't love Danny Boyle's direction; there were actually too many close ups that were too close up (I know, I'm complaining about close ups of Michael Fassbender—I should go home), but Boyle (127 Hours) was able to pace the film just right, making three acts of people talking intriguing and exciting.Those three acts endeavor to give us some insight into Steve Jobs (Fassbender), the Apple icon. Each act takes place in the 30-40 minutes leading up to product launches, all pivotal moments of Jobs's professional life, as well as, it turns out, his personal life. The acts take place in real time, and each includes a flashback (woven into the real time construct; it's like the characters are sharing a memory) that offers some backstory and additional insight.

We meet the people who worked with Jobs, though saying the exacting impresario truly worked with others is maybe misleading; it's more like they all worked around one another. Jobs's colleagues include Steve Wozniak (an impressive and serious Seth Rogen (50/50)), who created computers in Jobs's garage; Andy Hertzfeld (the reliable Michael Stuhlbarg (Hugo)), a technician who had a tumultuous professional and personal relationship with Jobs, but who didn't; Joanna Hoffman (a tough Kate Winslet), who is Jobs's self-described "work wife," and is the only one, it seems, who can stand up to Jobs and really get through to him; and John Sculley (Jeff Daniels (The Newsroom)), the one-time Apple CEO who was integral to Jobs's ouster from the company but also, at times, served as a father figure for Steve, complicating matters.

We meet the people who worked with Jobs, though saying the exacting impresario truly worked with others is maybe misleading; it's more like they all worked around one another. Jobs's colleagues include Steve Wozniak (an impressive and serious Seth Rogen (50/50)), who created computers in Jobs's garage; Andy Hertzfeld (the reliable Michael Stuhlbarg (Hugo)), a technician who had a tumultuous professional and personal relationship with Jobs, but who didn't; Joanna Hoffman (a tough Kate Winslet), who is Jobs's self-described "work wife," and is the only one, it seems, who can stand up to Jobs and really get through to him; and John Sculley (Jeff Daniels (The Newsroom)), the one-time Apple CEO who was integral to Jobs's ouster from the company but also, at times, served as a father figure for Steve, complicating matters.There's also the complex relationship between Jobs and Chrisann Brennan (a fragile Katherine Waterston (Inherent Vice)), his one-time girlfriend. In the first act, we learn that Jobs has denied paternity of Chrisann's daughter, Lisa (different actresses at different ages), yet he provides some financial support despite providing no emotional support. Over the course of the three acts, we see how Jobs's relationship with Lisa changes, and how he's changed by it, just as his relationships with the other people in his life evolve.

I was particularly taken with Michael Fassbender's ability to show someone who is arrogant, but feels he has a

right to be so; someone who is not intentionally smug, but just so

fixated on his view, and his tasks, and his objectives that he can't see

everything that's in his life. Fassbender (Hunger, 12 Years a Slave) is an incredibly attractive man, and in interviews he can come off as a charming bad boy, but there was not a trace of that in his performance. It's a different kind of charisma, something deeply rooted in Jobs's sense of self. Through Fassbender's performance, it's easy to see how one could become a Jobs acolyte, and just as easy to see how one could become disillusioned with the idol.

I was particularly taken with Michael Fassbender's ability to show someone who is arrogant, but feels he has a

right to be so; someone who is not intentionally smug, but just so

fixated on his view, and his tasks, and his objectives that he can't see

everything that's in his life. Fassbender (Hunger, 12 Years a Slave) is an incredibly attractive man, and in interviews he can come off as a charming bad boy, but there was not a trace of that in his performance. It's a different kind of charisma, something deeply rooted in Jobs's sense of self. Through Fassbender's performance, it's easy to see how one could become a Jobs acolyte, and just as easy to see how one could become disillusioned with the idol. Of course, I thrilled over the Sorkinese. Oscar winner Aaron Sorkin (The Social Network) crafted a screenplay that employs many of his trademarks, from the dense dialogue to his "I'm not other people" trope, and he once again shows off his knack for making music out of spoken words. His rhetorical balance, the way he chooses just the right words to express something, plants seeds in the first act that have not just an aural payoff in the end but also help to reveal character—it's music to my ears.

That is all punctuated by incredible sound design and scoring, serving as lush orchestrations to support Sorkin's original melody line. I'm thinking in particular of the second act, when Jobs and Woz step into the empty orchestra pit at the San Francisco Opera House, home to the San Francisco Ballet. As soon as they enter, we hear those unmistakable sounds of an orchestra warming up. Jobs, talking about innovation, starts speaking of Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring," and the differences between the immediate reactions to the score and ballet and what is now their revered place in history. As he speaks, and as the conflict between Jobs and Woz (and later Sculley) builds, "The Rite of Spring" can be heard, reaching its crescendo as the action does.

And it really is action. Sure, it's just people talking, but those people are all fantastic actors and they are discussing the things that are most important to their characters. Whether it's the technology they've created or are trying to promote and protect, or the people who are, like it or not, for better or worse, in their lives, these people are essentially fighting for their lives, for their pride and legacy. It's a thoroughly engaging story that gets at the heart of the trappings and triumphs of being a successful innovator.

Comments

Post a Comment